The fatal attack on Sir David Amiss MP understandably sent shockwaves through Parliament.

Now that the trial had rightfully concluded that the individual responsible was guilty of a terrorist attack and sentenced him to full life term, it is appropriate to review whether any lessons have been learned.

There have been four attacks on UK Members of Parliament since the beginning of this century, three of which resulted in a fatality, and one genuine planned attack that was thwarted.

There are significant patterns and trends in the attacks, which should make the protective security more effective, however this article will argue that that is not the case and that another fatal attack is likely.

This article will review the attacks, based on open-source material together with some personal knowledge and argue that whilst more than £3 millions of taxpayer’s money is spent annually on MPs security, they are no safer today that they were at the beginning of the century.

Background:

History is littered with political assassinations. In more recent times these incidents have become etched in the public’s minds and have changed the political landscape, impacted democracy, and harmed the public’s faith in the political processes. When these events are announced, they form historical moments in time. Whether it was the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Junior or more recently and closer to home, the murder of Jo Cox MP, these events, all of which could have been prevented, stopped significant political figures from reaching their potential.

The murder of Jo Cox MP was the first sitting Member of Parliament (MP) murdered in office by an individual, who was not part of a terrorist group, for many years. It occurred during the campaigning period that led up to the European referendum and may have changed politics in this country forever. Prior to her murder, many politicians had been suffering in silence, living with the ritual of daily abuse and threats and assuming this was just part of the job. It wasn’t and never should have been. But truth be known, no-one really knew or understood the extent of the situation nor had any real insight into what to do about it. That all changed on that day. (Saner, 2016)

In a briefing sent following the murder of Jo Cox MP to the National Police Chief’s Council (NPCC) in the UK, Assistant Commissioner Basu acknowledged that the role of an MP does present vulnerabilities and risks to allow our open democracy to flourish (Basu, 2016a)

Most recently, we have seen heightened tensions resulting from the Brexit debate and elements of the far right targeting prominent MPs such as Anna Soubry MP, routinely using terms such as ‘traitor’ and ‘Nazi”. These highly emotive terms have the capacity to cause fear amongst the MPs and possibly inspire others to take more violent action. (Allegratti & Heffer, 2019; Davies et al., 2019)

Threat assessments and the subject of targeted violence date back to the 19th Century France and Italy where the work of Laschi & Lombroso was well known and suggested that criminals could be identified based on physical defects. More recently research has been directed by issues of mental disorder and driven by those from the world of psychiatry and psychology. (Reid Meloy et al. 2012a) This changed in the late 1990s when Fein and Vossekuil were tasked by the US Secret Service to research all assignations and attempts, to ascertain what could be learnt from them and how this might change their operational approach. This project, which is now widely known as the Exceptional Case Study Project (ECSP) started considering targeted attacks, a term created by them, from a security rather than a mental health perspective, and has been referred to as one of two highly influential studies in its field. (Fein & Vossekuil, 1997; James, 2010) The other being Dietz and colleagues who examined letters written to members of the US Congress. (Dietz et al., 1991)

Threats to public figures have been the subject of different methodological studies since the mid 1980’s. These studies have primarily emerged from the United States of America and Europe and as such have usually focussed on those regions of the world. Initially, much of this work was focussed on stalking (Meloy, 1998) and the pursuit of celebrities and politicians by inappropriate and threatening letters by those with mental disorder. (Dietz & Martell, 1989) The subject of actual attacks on political figures was significantly advanced when Fein and Vossekuil published their Exceptional Case Study Project (ECSP) on Preventing Assassinations on behalf of the US Secret Service, who are tasked with protecting the office of the President of the United States. (Fein & Vossekuil, 1997) The subject was then advanced again by the work of Calhoun and Weston who by introducing terms such as ‘hunters and howlers’ sought to identify the differences between those to communicate with the intention of instilling fear and those whose intention is to attack and cause harm. (Calhoun & Weston, 2016)

In 1989 Dietz and Martell argued that public figures were ‘Presidents, Members of Congress, Governors, the leaders of social movements, and entertainment celebrities’ It was quite clearly very US centric and had a clear agenda to study the mentally disordered. This was the first in depth study of its time and stimulated an area of research that this paper continues. (Dietz & Martell, 1989)

The paper was written by two members of the scientific community, from the worlds of psychiatry and psychology and this set a pattern in which experts in those fields continued the research. From this point on, mental disorder has been a central tenet of all research, and in many ways, this is understandable as many of those publishing their research are from the same medical and scientific communities. The problem with this is that it has bias towards certain theories and is not always helpful to those working in the security fields. It is often very ‘suspect’ focussed rather than victim focussed and therefore comes at the theory of how to stop an attack from a very different perspective.

It is clear from the title that the focus is on the influence of mental health on the targeting of public figures. The intention is to identify the signals that the perpetrators leak to enable recognition of those at especially high risk of attacking, to enable an early intervention. The study identified an increase in attacks, suggesting that as many public figure attacks has resulted in injuries in the twenty-five years leading up to this study, as had in the previous one hundred and seventy-five years. (Dietz & Martell, 1989)

The paper researched those who target celebrities and those who target US Members of Congress. It was a comprehensive study used a mixed methodology of both detailed data and case studies drawn from both the files of the US Capital Police, tasked with protecting the US Congress and its Members and from the archives of Gavin de Becker, widely regarded as one of the leading experts in public figure protection in America. (Gavin de Becker and Associates, 2018). They state that every published incident where a public figure had been attacked was the work on a person who was ‘mentally disordered’ and go on to describe pre-attack warning behaviours such as inappropriate letters being sent, or visits being made. However, they go on to admit that many subjects who write inappropriate letters or visit pose no threats which has diminished the value of their identified warning behaviours. In their research they tell us much of their diagnosis is formed from reading subject’s letters to members of US Congress, which often formed no more than a few words and their findings suggest as many as 96% evidenced mental disorder. The statistics give considerable weight to their argument; however, the numbers researched amount to a random sample of 86 persons known to US Capitol Police to have written inappropriate letters to members of US Congress. It doesn’t define ‘inappropriate’ but knowing they have been investigated and based on the research it has to be asked what part bias played in these findings, and the relevance of it? (Dietz & Martell, 1989)

The Exceptional Case Study Project (ECSP) was tasked by the US Secret Service and written by Fein & Vossekuil in 1997. It is an operational study in which they identified and analyzed 83 persons known to have engaged in 73 incidents of assassination, attack, and near-attack behaviors from 1949 to 1995 in a mixed methodological project. Again, the numbers involved are small, however whilst this could diminish the value of the research, in its defense it did research all incidents that had occurred. ECSP is a key document in the research of violence towards public figures and is possibly the most cited document. This may be because Fein & Vossekuil, whilst unable to interview more than 20% of the attackers, did have access to the US Secret Service case files and were able to gain greater insight than many of their contemporaries. (Fein & Vossekuil, 1997)

One area that the ECSP is at odds with the British research is the venue of attacks. This contrast may be cultural, in that the way British MPs carry out their duties may conflict with those in the USA that the ECSP studied. Current practice continues to enable a local constituent to meet with their MP, in private, to discuss a specific issue and increasingly with a member of staff present. This is considered to put the MP and their staff and possibly other visitors in a highly vulnerable position.

The ECSP takes a very different view on the role of mental disorder.

The purpose of the study was to consider the problem from a law enforcement perspective, seeking to gather and develop knowledge that could be put to practical use. They focused on identifying those who posed a threat and how to intercept them. They concluded that there was no profile that described assassins and that whilst 61% had be treated at some point in their life for mental disorder, only 43% were delusional at the time of the attack. They go on to state that of those who had demonstrated previous mental disorder, less than 50% had been treated for it in the twelve months preceding the attack. What cannot be accounted for is, despite acknowledging that most attacker’s lives were on a downward spiral at the time of the attack, how many of the 48% might not have attacked had they had treatment in that twelve-month period.

They concluded that mental disorder rarely plays a part in what they coined ‘targeted attacks’ and that the pre attack behavior demonstrated rational thinking, which they argued diminished the relevance of mental disorder.(Fein & Vossekuil, 1997). This, James, Meloy and others tell us has more to do with how they considered mental disorder from a legal perspective as opposed to from a clinical one. They argue that the behaviour that Fein & Vossekuil call rationale would be considered strong evidence of psychosis in Europe. They go on to argue that this has much to do with the legal framework, and that because in the USA there is limited access to healthcare and legal powers to detain those with mental disorder, there are less options open to the mental health services to intervene. In contrast to the European model, where free health care and mental health services are widely available, and a legal framework allows detention to enable treatment, the subject of mental disorder is interpreted differently. (James, Mullen, et al., 2007) Clarke, takes another and perhaps more cynical view, arguing that the mental disorder theory is one biased by psychiatrists and politicians who have decided that such attacks evidence the presence of irrationality from what he termed ‘highly selective and questionable presentations’ (Clarke, 1982)

The ECSP identified that assassins are rarely spontaneous but plan their attacks and are driven by different personal motivations. They concluded that far from suffering from mental disorder they were driven by one of more of the following motivations.

- To achieve notoriety or fame

- Avenge a perceived wrong

- End personal pain…suicide by cop

- Bring national attention to a perceived problem

- To save the country or the world

- To achieve a special relationship with the target

- Money

- Bring about political change

However, whilst adding that these attackers are rarely driven by political motivation, it could be argued that numbers four, five and eight can all be political. This theory is corroborated by a report published in the Journal of Forensic Science in 2002 which in this case recognized the political aspect. (Scalora, Mario & V Baumgartner, Jerome & Zimmerman, William & Callaway, David & Hatch-Maillette, Mary & Covell, Christmas & E Palarea, Russell & A Krebs, Jason & O Washington 2002)

An important theory proposed by Fein and Vossekuil was that those who make threats don’t necessarily pose them. (Fein et al., 1995) They corroborated this in the ECSP where they found that none of the attackers studied communicated a direct threat to the target directly or to law enforcement. In terms of the purpose of the project it directed that attention should be focused on those who pose a threat, whether they have made a threat. (Fein & Vossekuil, 1997) This finding is supported by the study into the role of mental disorder in attacks on European politicians 1990-2004 where they could find no evidence that the person targeted was subject to a direct threat. (James, P. E. Mullen, et al., 2007) Human behaviour is more complicated, and it would be risky for a security manager to assume this theory as always true as a person of concern (POC) who threatens can also attack (Scalora et al., 2003) and the Fixated Research Group argued that those who breached the security were more likely to be a threat than those who simply approached. (James, D.V., Mullen, P.E., Pathé, M.T., Meloy, J.R., Farnham, F.R., Preston, L., Darnley, 2006)

Calhoun & Weston went on to provide a term for this theory, ‘Hunters and Howlers’ and suggested that “Hunters Hunt and Howlers Howl” (Calhoun & Weston, 2016) These terms are somewhat simplistic and misleading as whilst in general it can be said to be true, some who ‘howl’ stop, and start to ‘hunt’ and there will be some examples where an attacker has previously made a threat, as it leaked it to another but not directly to the target. Equally if this concept was 100% accurate, it would be very easy for a potential attacker to make a direct threat to persuade law enforcement that he was not actually posing a threat, only to enabling him to do so. This was expanded upon by Warren et al who further differentiated into five types of threateners:

- Screamer: – whose threats are usually expletives, made emotionally and in the moment, in context to the situation where the target of their threats understands that no harm is intended.

- Shockers: – these threats are intended to induce fear and have an immediate impact and often used against those who are dominant over them.

- Shielders: – this is a defensive threat, intended to ward off an aggressor

- Schemers: – these are conditional threats, intended to influence or coerce and promise to engage unless the other person complies.

- Signalers: – these promise a future harm to the target. They state an intention to harm. (Warren et al., 2014)

Whilst all threats can induce fear, and often that is their only intention, the signalers promise or threaten future harm, Warren et al argued that those who genuinely intend future harm rarely signal that intention and put themselves at a disadvantage. What is known, is that threats can be veiled and infer violence and whilst they induce fear, they are no more likely to be acted upon than direct threats. A direct threat has been defined as ‘an unambiguous statement to a target or to authorities of intend to do harm’ The theory that those who make such threats not posing a threat is increasingly true the more distant the relationship is between the two parties. Equally, where an element of intimacy exists, whether real or perceived, the threat increases. (FBI, 2017) Almost exclusively, studies found no relationship between direct threats and attacks on public figures, however what they did find was that quite often the attacks were preceded by warning behaviors. (Warren et al., 2014)

Developing from the theory of Hunters, Meloy argues that this can be explained by two differing types of violence that separate those who attack a politician as opposed to those who engage in ‘everyday’ violence. Termed as either Affective or Predatory violence, one highly emotional and the other cold and calculated, they have very different purposes. Affective violence is highly emotional, with a sense of arousal, anger, or fear. This is ‘everyday’ violence seen in street fights, domestic violence, and gang murders. Other terms used include impulsive, reactive, hostile, and self-protective. Predatory violence is not preceded by emotion. In fact, it is the lack of arousal and emotion and the presence of cognitive planning that separate it from the everyday violence we are all too familiar with. Other terms used are premeditated, proactive and cold blooded. The purpose of affective violence is to defend oneself against a perceived threat. There is a growing body of evidence that psychopaths are more likely to engage in predator violence. This can be seen in stalkers. Intimate stalkers who turn violent threaten their victims and when they attack are often impulsive, choking, pushing, punching, and pulling hair. Public figure stalkers plan their attack, rarely threaten (less that 5%) and often use weapons. Predatory behavior, once necessary for survival, is now used to satisfy other needs such as to achieve notoriety, wealth, dominance, and revenge. Very often the predator will express a complete lack of any emotion during the attack. (Meloy, 2006)

The theory of pre-attack warning behaviors is a key element of this dissertation and has been widely written about. A prominent publication by Meloy expanded on this theory previously touched on by others. (Reid Meloy et al. 2012b) The term ‘warning behaviors’ was used to suggest that the POC had changed their behaviour and was on a period of acceleration towards the attack. They do not predict who is going to attack, but they do suggest an increasing threat. They can be useful to help threat assessors manage low frequency intentional acts of violence towards an identified target.(Calhoun & Weston, 2016) In the previously referred to research into attacks on European politicians, 46% showed signs of the warning behaviors before their attacks. (James, Mullen, et al., 2007) The theory argues that there are eight warning behaviours. It doesn’t suggest that they all will or need to be present, but clearly the greater the cluster, the greater the threat:

A fundamental premise of this theory is that attacks are too rare to predict statistically, leading us to focus on approach behaviour as a precondition to attacks. Whilst these typologies provide a welcome structure and would appear to help to identify behaviour that might signal a POC, Meloy himself recognised that one of the issues with such theories is that much of it requires the POC to have been identified in advance or the theory administered in hindsight which leads to suggestion that cases can be ‘adapted and deformed to fit the category’ (J. Reid Meloy et al. 2008) It is suggested there are eight pre-attack warning behaviours.

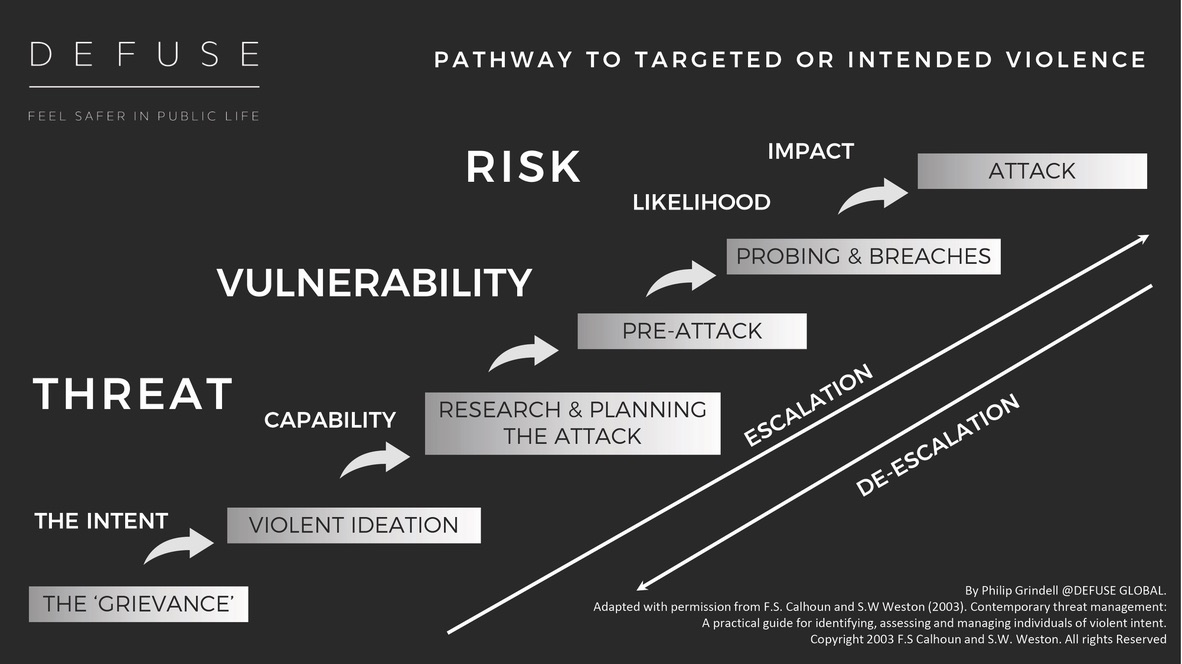

1.Pathway to violence: This is described as the period in which the POC researches and plans the attack. Calhoun & Weston went further and created an entire model based on this behaviour. Their model argues that the POC travels along this path, initiated by a grievance, real or perceived, which then leads them on to the idea that violence is the only way to resolve this issue and from there they start to research and plan the attack. This grievance can be either personal or ideological. The POC can move along the model escalating or de-escalating the threat depending on several variables.

Fig.1 (Calhoun & Weston, 2003)

The concept of ‘a pathway to violence’ does have some corroboration. Fein and Vossekuil refer to the attacker being on a pathway when they stated that an assassination is the result of a process. (Fein & Vossekuil, 1997) Once a grievance has occurred and the subject had decided that violence is the answer it follows that they will then start to research and plan what to do next. In the ECSP they found that 67% of the subjects had a grievance at the time of the incident and more than 80% who had a grievance blamed their target for it. However, they also stated that the attacker often considered more than one target before deciding who to attack. (Fein & Vossekuil, 1997) Whilst not explicit, there is no indication that once on the ‘journey’ the subject cannot change their mind and stop at any time, so it is not as prescriptive as first thought. This theory is questioned in the research on stalkers of the British Royal family where is states that ‘there is little evidence to support the contention of there being a logical sequence of behaviors’ (James et al., 2010).

- Fixation warning behaviour: This is described as an increased pathological preoccupation with either a person or an ideology or cause. Fixation can be a normal part of life, such as the emotion of loving, however when that fixation then consumes your every waking moment and becomes obsessive, it becomes pathological and is often linked to stalking behavior. From a security perspective this can be difficult to identify, however an unnatural volume of interest may be an indicator. One of the risks attached to such fixation is the need for proximity and when this is frustrated it can metamorphize into strong emotions of anger and emotionally hijacks their lives. (Paul E Mullen et al. 2009)

- Identification warning behaviour: this is described as behaviour that suggests a psychological desire to be a ‘pseudo-commando’ (Reid Meloy et al. 2012b; Dietz 1986) This is often associated with those who consider themselves to be ‘soldiers’ of a cause and dress up in military style outfits. (J Reid Meloy et al. 2015) A good example of this is Anders Behring Breivik who dressed up in military uniforms, identified himself as a Commander in the Knights Templar and considered that he was fighting a cause. (J. Reid Meloy et al. 2015) The research suggests POC who demonstrate this behaviour have emotions of anger and resentment. (Knoll, 2012) Another sign of this behaviour, corroborated by the ECSP, is the association and research into the actions of other attackers. The POC will have researched other attacks and seek to link himself to that attack or gain confidence from it. (Meloy, Mohandie, et al., 2015) Meloy argues that there are five characteristics of identification warning behaviour: ‘Pseudo-Commando’ described a person preoccupied by firearms who commit their attacks after long period of contemplation. The ‘Warrior Mentality’ is demonstrated as the fantasy and behaviour of being a soldier/warrior, often with the goal of targeting civilians, as opposed to be an actual soldier in a conflict. The ‘Association with weapons, Law Enforcement or Military Paraphernalia’ is the third identifiable behaviour in which the weapons can either be real or virtual and may include participating in relevant online first-person shooter games. The ‘Identify with Other Attackers or Assassins’ is one where it may be a real of fictional assassin and may include associating themselves with a mystical hero. Becoming an ‘Agent to Advance a Particular Cause or Belief System’ is where they may be assuming the role of a soldier fighting to support their ideological beliefs, this can be a cover to hide their desire for fame and notoriety.

- Novel Aggression warning behaviour: This is best described an act of violence or aggressive behaviour in which the POC is testing their ability to act in such a way. It is usually unrelated to the ‘pathway’ on which they are travelling and can be totally out of character. The act may be completely unrelated to what they intend on doing and property crimes may be an indication. (FBI, 2017)

- Energy Burst warning behaviour: This is a key indicator that the intention is escalating and can occur in the hours, days, or weeks before the actual event. It is characterised by an increase in pre-attack activity and can be signs of final preparations, purchasing equipment or conducting hostile reconnaissance or internet activity.

- Leakage Warning behaviour: This is where the POC communicated their intention to a third party. This can be done in person, online, in a journal or letters. A vivid example is the videos released by the 7/7 bombers after their attacks on London. Meloy suggests that this concept was first mentioned by O’Toole in her study of school violence in 2000. (Reid Meloy et al., 2012a) This is inaccurate as it was very clearly described in the ECSP where their research identified that 78% of those researched either spoke or wrote about their target before they attacked. (Fein & Vossekuil, 1997) In Meloy’s defence he argues that one of the issues about Leakage is in its definition, and he does acknowledge the ECSP. The FBI defined leakage as ‘including a wide range of both direct and indirect forecasting behaviours underpinned by different and/or multiple motivations’ It further included incidents where the POC attempts to pursued friends or family to assist in the preparations, although they admit this is often unknowingly Meloy suggests that his research into leakage should not be interpreted to suggest that the POC leaks with the intention that someone may stop them. (Meloy & O’Toole, 2011)

- Last resort warning behaviour: This behaviour is evidenced by language of no hope. It suggests that the POC sees no alternative, and nothing left to live for. It is an indication of a view that there is no alternative other than violence and seeks to justify the action. (De Becker, 1997) It can also be witnessed by reckless behaviours which show no concern for future consequences. (FBI, 2017)

- Directed Communicated threat warning behaviour: This behaviour has been covered in detail within the theory of those who make threats don’t pose them. As such it is interesting that Meloy suggests that this is a warning behaviour as this is widely contradicted and to some degree discredits the entire theory. In fact, it was Meloy himself that suggested that direct communication in public stalking cases may be a risk reducing factor. (J. Reid Meloy et al. 2008)

Drs Reid Meloy and Paul Gill assessed the prevalence of each indicator across the 111 lone-actor terrorists to ascertain the prevalence (Meloy & Gill, 2016)

The case studies of the attacks on serving MPs this century. Three of the attacks resulted in fatalities and the fourth in very serious and life-threatening injuries. They have all occurred since the turn of the century and have been committed by a single attacker acting apparently alone. The purpose is not to review the subsequent investigations nor to find or apportion fault with anyone. The responsibility for these incidents lies very clearly with the offender, who in all three cases was arrested and prosecuted. The purpose is to overlay the theories against the three case studies and analyse whether the theories are relevant and if so, can they be relied upon to help prevent future attacks. A summary of each case will be outlined, followed by the findings against the relevant theories.

Case Studies:

- The attack on Nigel Jones MP (now Lord Jones) by Robert Ashman, which killed Andrew Pennington on 28th January 2000.

- The attack on Stephen Timms MP by Roshonara Choudhry on 14th May 2010

- The fatal attack on Jo Cox MP by Thomas Mair and the serious wounding of Bernard Carter-Kenny, on 16th June 2016

- The planned attack on Rosie Cooper MP by Jack Renshaw in 2017

- The fatal attack on Sir David Amess by Ali Harbi Ali in 2021.

The five attacks have some immediate similarities, in that they were all attacked by a single attacker and at or in the proximity of their Constituency surgery and all committed by a local constituent or in the case of the attack on Sir David Amess, purported to be a local constituent. Equally, whilst the motivations were different, they were all driven by a fixated grievance.

For the purposes of clarity, each incident will be summarised and following that the theories previous discussed will be then tested against the case studies along with other emerging issues.

Nigel Jones (NJ) was the Liberal Democrat MP for Cheltenham when he was attacked.

Robert Ashman was a local constituent who was well known to NJ

The story of how Robert Ashman’s life spiralled out of control and subsequently led him to attack his local MP had all the hallmarks on a break down. He went from being an articulate, successful middle-class professional family man to a ‘deranged’ killer. He had, over a course of several years, sought help from NJ somewhere between 50-100 times, regularly attending Friday surgeries. During these meetings NJ provided a character reference for Ashman when he was held accountable for his actions. Finally, having lost his career, his wife and family and his home, he found himself living in a bedsit, working as a barman and bankrupt. He had been in legal disputes with almost every agency he had come across with recorded episodes of violence, when he decided that his local MP was part of the conspiracy against him, and once again visited the Friday surgery, but this time armed and intent on killing him. He asked to see the MP and was escorted into the office. He was wearing an overcoat, underneath which, hanging from his neck was a Samurai sword which he had taken from his Father house during lunch. He was later described as mumbling to NJ before undoing his coat and pulling out the sword with which he attacked NJ who was able to swivel avoiding the initial assault and then grabbed the sword by the blade. Ashman twisted the sword causing serious wounds to NJ’s hands. It is believed that it was at this point that Andrew Pennington, the MP’s assistant hit Ashman over the head enabling NJ to run out of the office. Ashman then turned the sword on Pennington inflicting fatal injuries. He then left the surgery and walked down the road where he was arrested. (Savill, 2001) He was found to be ‘unfit’ to stand trial and detailed at a secure unit.

Stephen Timms (ST) is the Labour MP for East Ham.

Roshonara Choudhry was a twenty one year old Bangladeshi Muslim and a local constituent at the time of the attack.

She had recently subjected herself to online radicalisation and followed extremist beliefs.

Choudhry, who was from a poor Bangladeshi/English family, living off benefits and described as being as being moderate Muslims. She was a gifted student and was succeeding. It was whilst she was studying English at King’s College, London that the first signs of change were apparent. In November 2009 she began to listen to a radical jihadi preacher, Anwar al-Awlaki, on the internet, and later watched YouTube videos of others such as Sheikh Abdullah Azzam. It was whilst watching and listening to these extremist preachers that she became radicalised and decided that she had a duty to commit the attack. (Gill 2015; Fredholm 2016)

Choudhry researched several MPs that had voted for the war in Iraq. She decided on ST for several reasons, one of which was that he was her local MP and as such she would have easier access to him. She made an appointment to see him at his surgery and on Friday 14th May 2010 she attended made Beckton Globe community centre in Newham, East London to carry out her attack. Once at her appointment, ST directed her to sit down opposite from him, instead Choudhry walked around the desk, reached out with her left hand as if to shake his, and stabbed him with a knife she had in her right hand. She stabbed him twice before being pulled away by an assistant. Having been detailed, she was subsequently arrested by Police. ST was taken to hospital and following emergency surgery, recovered. (Carter, 2013) Choudhry was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Jo Cox (JC) was the Labour MP for Batley and Spen, a position she had held for just thirteen months.

Thomas Mair was a local constituent who was said to be an unemployed gardener with long term extreme right-wing views.

On Thursday 16th June 2016 JC was in her constituency, campaigning for the forthcoming European referendum. She was an ardent ‘Remainer’ and pro-European. At about 1pm she was on her way to a constituency meeting in Birstall, West Yorkshire.

Mair was described as a loner, who lived alone and had long term mental health issues. He had a long history of extreme far right views and had ordered literature from as far away as the USA. He had previously written letters and published material supporting the South African apartheid regime and whilst he was not a member, is believed to have had links with UK based far right groups. JC was pro-immigration. (BBC News, 2016)

On the day in question, JC got out of her car and together with two of her assistants walked towards the venue of their meeting. She was attacked by Mair, armed with a firearm and a knife. As he attacked her, and those who came to her aid, he shouted, ‘this is for Britain”, “keep Britain independent” and “Britain first”. Having initially begun to walk away, he returned to the scene when he realised that JC was still alive, and calmly executed her while she lay on the ground. In total JC was stabbed fifteen times and shot three times. Mair walked away, before being arrested by Police less than a mile away, to whom he stated “I am a political activist”(Himelfield, 2017; Taylor, 2016) He was convicted and sentenced to a full life term.

Rosie Cooper MP (RC) is the Labour Party politician for West Lancashire.

In June 2017 Jack Renshaw (JR), a member of the prescribed neo-Nazi group, National Action, shared the details of an attack he was planning. JR was at the time, under investigation by Lancashire Constabulary’s Detective Constable Victoria Henderson on suspicion of downloading child pornography. He has been arrested for several offences in the past, including stirring up racial hatred in January 2017, while belonging to the British National Party (BNP) Youth division.

- He explained to his ‘comrades’ that he planned to kidnap RC and then call in DC Henderson as a hostage. He would then kill both ladies before he intended ‘martyring’ himself by suicide by cop. Renshaw’s plan had included buying a 19in (48 cm) Gladius knife, studying Cooper’s itinerary. (“Jack Renshaw Admits Planning to Murder MP Rosie Cooper,” 2018)

The plan was leaked by whistle-blower Robbie Mullen. This leaked information was reported to the Met Police’s Parliamentary Liaison and Investigation Team (PLaIT) where I was able to identify that there were several of the previously discussed indicators. The subsequent investigation by NW CT unit identified that Renshaw has equipped himself with a machete as part of his planning.

On 17 May 2019, the judge sentenced Renshaw to life imprisonment, with a minimum term of 20 years. (MP Death Plot Neo-Nazi Jailed for Life, 2019)

Sir David Amess MP (DA) was the Conservative MP for Southend West.

Ali Harbi Ali (AHA), 26 was a self-confessed member of ISIS. On 15 October 2021, DA was stabbed multiple times at a constituency surgery in Leigh-on-Sea and later died at the scene from his injuries. Ali was arrested at the scene.

From May 2019 AHA researched and planned attacks on Members of Parliament and the Houses of Parliament. This included specific trips to a constituency surgery of Mike Freer MP and the home address of Michael Gove MP. On his home computer there were multiple searches and webpage results relating to MPs and their surgeries. Investigations showed that AHA undertook reconnaissance near Mike Freer’s surgery on 17 September 2021, and Michael Gove’s home address on four occasions in March and June 2021. A staff member at one of Mike Freer’s surgeries identified a man who matched AHA’s description as staring into the building. CCTV footage also captured AHA performing reconnaissance of the area around the Houses of Parliament on 16, 20 and 22 September 2021.

AHA had used a false address to deceive the DA’s staff that he lived in the local area and made the journey from London to Leigh-On-Sea armed with the large kitchen knife that was used in the attack.

AHA told witnesses He told them the attack had been planned and that he wanted to kill every MP who voted for bombings in Syria.

Ali Harbi Ali was sentenced to a whole life tariff at the Central Criminal Court. (The Crown Prosecution Service, n.d.)

Summary of Findings

None of the subjects who went on to attack in our case studies demonstrated any communicated threats or inappropriately behaviour towards their target.

Whilst Ashman knew and regularly visited NJ, at no point is there any evidence that a direct threat of any description was made.

Whilst Choudhry did not know ST, she claims to have met him some years earlier and there is a suggestion that she applied for support from him in respect of a financial claim which was declined. Again, there is no evidence or suggestion that any direct threat was made.

With respect to Mair, there is no evidence that he corresponded or made any threats towards JC.

There is no evidence or suggestion that KR had any communications with RC.

There is no evidence or suggestion that AHA had any communications with DA, albeit he did book a meeting with him via DA’s staff.

In line with these cases, it could be argued that the case that those who pose a threat rarely make a threat could be made, however whilst in general those who pose threats don’t make them, and arguably why would they? In a recent interview on The Online Bodyguard Podcast®, Dr Meloy stated that the extensive research that communicated direct threats were found in less than 5% of cases.

Why would they want to publish their intentions and risk being caught or stopped from their intended action? (Meloy & Hoffmann 2014)

In respect of the Pathway to Violence, there is little evidence to suggest that Ashman spent any significant time or effort planning the attack. His father has stated that, during his lunch visit prior to the attack, Ashman had been reading the ‘Gray’s Anatomy’ book before taking his father’s Samurai sword, which he used during the attack. (BBC News, 2000) When we consider this from the perspective of Calhoun and Weston’s model, it could be argued that Ashman formed a grievance, and certainly formed to ideation of using violence. His research may have been reading Gray’s Anatomy and taking the weapon was the pre-attack preparation. His probing and breaching were achieved because he was already known, and he then attacked.

When we compare this to the other cases, we can see that there were far more signs of them being on this pathway.

Choudhry was a successful student, who suddenly dropped out in her third year, when one of her lecturers was expecting her to achieve a first-class honours degree. She had by this time become self-radicalised by watching videos and downloads of extremist preachers. It was through this process that she developed the grievance, which related to the persecution of Muslims, and this may have included her own father who was unemployed. She went into a phase of research and planning. She researched which MPs had voted for the war in Iraq and identified a few. Interestingly, one of these was a Jewish MP who may have been seen as an attractive target. However, she settled on Stephen Timms for several reasons. Firstly, he was her local MP so that made approaching and meeting him easier. Secondly, having researched his voting history she considered that he had no conscience and just went with his party. Having watched one particular video which, she interpreted to give her permission as a female to ‘fight’ she developed the violent intention. She then made an appointment to meet with her target and purchased two knives to use in the attack. On the day of the attack, she paid off her student loan and emptied her bank account. This was to ensure that her family could not be liable for any debts and to prevent the government from seizing her funds. Having made an appointment, she effectively breached any security measures. It could be argued this was such is out of sync with the Pathway theory. She then attacked. (Carter, 2013)

Mair, with his extreme far right racist views, had a grievance. It has been suggested that the Brexit campaign may have stoked up these views. Mair is known to have conducted online research into both Jo Cox and William Hague, who were both prominent and vocal pro-immigration and EU Yorkshire based MPs. Again, it may have been because Jo Cox was his local MP or because she was representing the Labour party or because she was a woman that caused him to choose her over William Hague. (Cobain et al., 2016) He must have conducted further research to know where and what day and time Jo Cox was holding her surgery, and possibly what car she would be arriving in. This enabled him to breach any security she may have had and ambush her on the street. In sentencing Mair, The Honourable Mr Justice Wilkes concluded “there was a substantial degree of premeditation and planning’. You had, over a period of weeks, researched your intended victim, you had researched the firearm which was modified to become a handgun. You made inquiries about its ability to inflict fatal injury and you sought instruction on how to use it in that modified form. You informed yourself about previous murders of civil rights workers and a past assassination of a serving MP. You contemplated the aftermath, researching lying in state arrangements. You even researched matricide knowing that Jo Cox was the mother of young children. You planned your escape from the scene by adopting a form of disguise to put off those searching for you and, during your escape, you reloaded the firearm ready for any eventuality. Finally, as the jury has decided, you fully intended to kill Jo Cox” (The Honourable Mr Justice Wilkes, 2016) It can be strongly argued that he travelled along a Pathway to Violence.

Renshaw is known to have extreme far right racist views and has previously been convicted on related offences. He was also under investigation for child pornography. In the summing of prior to sentencing the Judge made specific references to his “perverted view of history and current politics” and the fact that he had praised the attack on Jo Cox MP. She went on to reference the extensive research he conducted on RC, together with acquiring the weapon he intended using.

Ali’s grievance was, according to him, related to the bombing of Syria. He was also known to have conducted extensive research and planning, not just on Sir David, but other MPs. This is another common factor and is referred to as ‘Target Dispersal’. He booked an appointment to circumvent any security and armed himself before travelling to the attack location.

In terms of Fixation, all the cases have evidence of fixation. . In all but one case they were fixated on causes. Choudhry and Ali on the persecution of Muslims and on extremist Islamist ideology. Mair and Renshaw, from the opposite ideological viewpoint, was fixated on white supremacist views that non-whites were taking over and on the unfairness of this. What they had in common was the power of their fixations and their consideration that violence was only method of resolving or bringing these issues to attention.

Ashman’s fixation was different. He was consumed with a feeling of unfairness, but one that was very personally targeted at him. Such was the strength of his fixation he developed delusions and a persecution complex that there was a conspiracy against him. Ultimately, he believed that Nigel Jones MP had become part of that conspiracy and was going to ‘punish’ him for that. Ashman is the only attacker who was deemed unfit to stand trial through insanity, and it can be argued that he was the least predatory of off the cases.

The fixation on the issue of them being victims of unfairness runs through all cases.

Except for Ashman, it can be considered that all saw themselves as soldiers fighting for their cause. Whilst none adopted the identification and warrior mentality state of someone such as Breivik who dressed up in miscellaneous uniforms and suggested he represented the Knights Templar; they did believe in the fantasy that they were soldiers targeting an unarmed civilian as opposed to engaging in legitimate warfare. (Meloy, Habermeyer, et al., 2015)

Mair researched the actions of serial killers and public shootings, as well as how to make makeshift weapons, and we may never know whether this was to avoid making mistakes that they did, or whether it was connected to his identification to theirs. (Himelfield, 2017) He had a fascination with Nazi ideology and memorabilia as well as the apartheid regime in South Africa. (Cobain et al., 2016) There is evidence that Mair ticks 4 of the 5 characteristics and this may be connected to the length of time that he had to plan and his isolated personality type. There is less evidence on Choudhry and none that connects Ashman to this behaviour. Renshaw praised the actions of Mair, and it is likely that he researched and possibly was inspired by Mair.

Novel aggression was perhaps not relevant in Ashman’s case as he had a history of acting violently. It is known that Ashman had a short temper. Ironically it was NC that helped Ashman avoid a prison sentence with a reference when in 1992 Ashman attacked a tax collector, breaking his ribs. In 1994 a burglar who broke into Ashman’s property was threatened by Ashman, armed with a knife. He later appeared on the Kilroy television show encouraging others to take the law into their own hands. (BBC News, 2001) This warning behaviour appears less relevant in the others, bar Renshaw who had previous convictions nor a history of violence.

Energy Burst behaviour is an acceleration of activity as the predatory attack approaches. There is little sign of this in Ashman, but some distinctive evidence in both Mair and Choudhry. In the days before he murdered Jo Cox MP, Mair intensified his research, looking up information on the murder of Ian Gow MP, the last MP murdered, Matricide and the Klu Klux Klan and on the evening before he killed JC, he attended the local wellbeing centre asking about alternative therapies for his depression.(Cobain et al., 2016; Sommers, 2016)

Choudhry perhaps displayed more typical behaviour, consistent with the energy burst behaviour. He decision to attack and kill ST was made only a few weeks prior to the actual attack. (Gill 2015) Having decided upon her target, she began planning her attack, purchasing two knives, and making an appointment with ST. On the day of the attack, she left home, and took the bus to sort out her financial affairs (which can also be consistent with last resort warning behaviour) (Department of Homeland Security et al., 2012) Arguably everything she did, once she had identified ST as her target, can be considered to be evidence of energy burst behaviour and in these last few weeks there must have been signs of her behaviour changing.

Choudhry is in many ways the archetypal Lone actor. She was radicalised online and planned and carried out her attack without any communication or interaction or encouragement with anyone. When challenged about this by one of the investigating detectives she is quoted as saying that she hadn’t told anyone as they wouldn’t understand and equally, she didn’t wish to implicate anyone. (Simon 2016) The only sign of any potential leakage was a draft letter addressed to her mother, found on her computer, which tells of her hatred of living in Britain and desire to live in a Muslim country, declaring that she could no longer live under British anti-Islamic rule. Whilst the literal concept of leakage may not be immediately obvious, it might be argued that behavioural changes could have been missed. As has been previously stated, she was an excellent student who dropped out in her final year of her degree at King’s College London, where she was the top student, blaming the University for being un-Islamic. She stated in her interview that she came to this conclusion when they gave an award to Shimon Peres. This was compounded by the fact that the university also had a department for tackling radicalisation. In the same interviews, she went to talk about how she discussed Islam with her brothers and sister, although apparently not telling them everything. (Dodd, 2010) Whether this is true or whether the family’s ‘motivational blindness’ preventing from understanding what happening in front of them may never be known. However, research into how families and bystanders fail to notice what is apparently obvious is subject to ongoing research. (Rowe, 2018) In contrast, neither Mair or Ashman, perhaps aided by the fact they lived solitary lives, leaked any indication of what they were about to do, with Mair’s mother quoted as saying that she never saw it coming. (Sommers, 2016) Leakage is a common behavioural sign and yet one that almost non-existent in the three cases studied.

As mentioned, Choudhry’s settling her financial affairs is a classic sign of last resort behaviour. She has stated that she did this because she did not want the funds to be seized and go to the UK government and settled her debts so her family couldn’t be held accountable. These are the actions of someone who either thought that she would be killed or as happened, arrested, and sentenced to life imprisonment. Neither Ashman or Mair gave any such warning, perhaps as they had nothing to leave. Mair was a loner, but as neither he nor Ashman communicated threats towards their intended targets, there is no evidence of any last resort behaviour. Renshaw’s declaration that he intended to ‘martyr’ himself can be viewed as last resort language, however at this stage there is no such evidence in the case of Ali.

The topic of whether any of the three case studies demonstrated directed threats behaviour has been covered.

What is apparent from the grid below, is that the only warning behaviour that all of our cases had in common, was that of having a fixation. An interesting finding is that the fixation tends to be more focused on a cause than on an individual per se, and in four of the five cases, whilst several targets were considered, the MP was targeted primarily as they were the local MP which gave greater accessibility.

|

|

Ashman |

Choudhry |

Mair |

Renshaw |

Ali |

| Pathway to Violence |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

| Fixation |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| Identification |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

| Novel Aggression |

|

|

|||

| Energy Burst |

X |

X |

|

|

|

| Leakage |

X |

X |

|

||

| Last resort |

X |

X |

|

||

| Direct Threats |

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In respect of the eight warning behaviours, Ashman exhibited the least of all the warning behaviours.

This may be because he was suffering from an identified and diagnosed serious mental disorder and was the least predatory of all the cases studied or perhaps because his fixation was personal rather than ideological.

Whilst the issue of whether Choudhry leaked information can be argued, other than the last resort behaviour, she shared the remainder with Mair. That suggests that their predatory targeting of a MP does provide opportunities for intervention. Renshaw shared the second most indicators, and his attack was prevented whilst has few identified at this stage.

The question is how do we identify these behaviours before an attack takes place?

What we do know is each of these attackers had a fixation and that they saw that the only resolution was through extreme violence. The other commonality is that each of these attackers chose a similar location to target their victims, the advertised surgeries when they either made an appointment or knew that their target would be there.

Protective Security

Mindful of the millions of pounds of UK taxpayers’ money that is spent to prevent MPs from being attacked, how well is that spent.

The Protective Security measures come under the umbrella of Operation Bridger. (Basu, 2016b) Operational Bridger enables fully funded protective security measures for each MP at their residential address, the constituency office and where relevant, their London residence. The purpose of the security measures, all of which must comply with the Secured by Design specifications, are to prevent a physical attack. They are not to record an event, such as with CCTV.

The implementation of the measures is managed by the Parliamentary Security Department, with the Police engaging where there is an increased level of threat.

In 2019 security guards were introduced on a voluntary basis for MPs surgeries. It is perhaps an indication of the lack of this measure being implemented that following the attack on Sir David Amess, who did not have a security guard present, the Home secretary , Priti Patel MP and the Speaker of the House of Commons, Sir Lindsay Hoyle MP, issued a statement in which they announced “MPs have been offered trained security protection when meeting constituents following last week’s killing of Conservative MP Sir David Amess”. (MPs Offered Security Guards at Constituency Surgeries – BBC News, n.d.)

Personal experience of managing Operation Bridger is that despite the consistent threat being at the MPs surgeries, together with a legal duty of care for their staff and visitors (Baldwin et al., 2020) most MPs prioritise their security at home.

The risk at an MP’s surgery is recognised and there has been extensive work done to improve the security at these venues. The challenge is that every surgery is conducted differently, with hugely differing challenges between the urban and rural constituencies. However, there are some consistent advice that if followed, would significantly enhance the safety of all concerned. Sadly, that is often ignored.

British MPs are only required to meet with their own local constituents and should ensure that those who are afforded an appointment are genuine residents. Where a meeting is requested by a person unknown to the MP or their staff, research on that individual should be undertaken to identify who they are and a simple check with the local police will identify if there are any concerns. These checks are rarely conducted.

It is common to hear an MP state with confidence that ‘it won’t happen to me; I know my constituents”. The greatest threat to UK MPs is complacency, hence why their adherence to the advice and guidance is poor and despite the clear trend, they seek to protect their homes before their surgeries.

There is a distinct lack of understanding of the nature of the threat facing MPs, with some announcing they intend wearing body armour when in public and having concerns about their safety when it the supermarket. (Sales & Fielding, 2022)

Politicians are targeted by predatory attackers. Those who pose a serious threat do not demonstrate affective or impulsive violence nor do they conduct random attacks. Those who communicate threatening or abusive messages are extremely unlikely to pose a physical threat, and yet that is where a significant focus and media attention is placed.

When reviewing the MPs that have been targeted this century, none of would have been deemed high risk or outspoken. It is the location of the attacker rather than the MP that will define where the next attack will take place. That means that all MPs are at equal risk.

The next attack on a UK Member of Parliament is likely to follow the pattern of being or purporting to be a local constituent and is almost certainly going to take place in or close to a constituent surgery.

The attacker will invariably be or claim to be part of an extremist organisation and will have a fixation on an ideological global issue that causes them to feel excluded or angered. There is a high chance that they will have studied other attacks and have researched more than one target before settling on their local MP. They will be unconcerned with the consequences of their actions, be they life imprisonment or death, nor will they consider a lone security guard to be a deterrent.

The other trend will be that the attack will almost certainly have been preventable.